Marcus Hook survives and tries to thrive despite energy boom and bust

Driving along 10th Street towards Marcus Hook, Pa. from Delaware. The Marcus Hook Industrial Complex (formerly Sunoco Logistics) is on both sides of the road. The site was once a refinery but is now a natural gas hub with lots of extra space for other businesses. VIDEO BY MEG MCGUIRE

In our fantasy world, we have no fossil fuels being extracted or used and a much cleaner, healthier world.

Unfortunately, we have no magic wand to make this happen and the real world is complicated and confusing.

Marcus Hook is a small borough on the banks of the Delaware River, like any number of other towns on the river's 330-mile journey to the sea. It's not fancy, like some, nor large and metropolitan like others. It's plain and rather urban and home to 2,500 people.

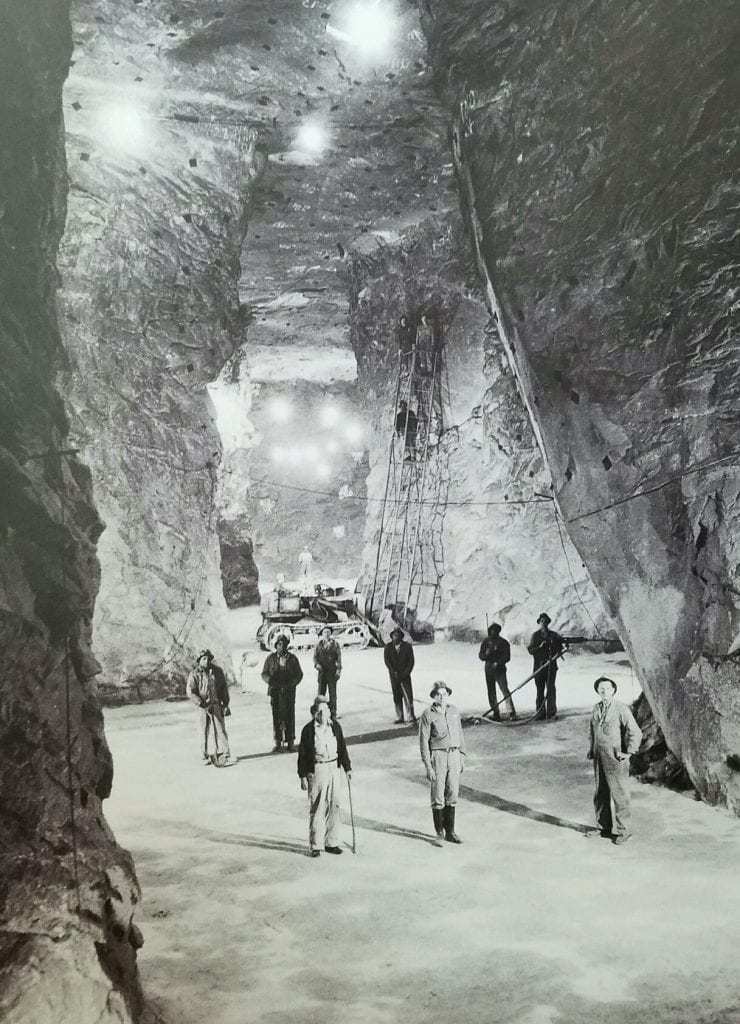

Marcus Hook's fortunes are inextricably tied to the energy industry. Pipelines end here. Trucks and trains come and go. Ships dock here from all over the world. Built on granite, its vast underground storage caverns can house millions of gallons of natural gas liquids.

It sits, as many Delaware River towns do, at the crossroads of cultural, economic and environmental forces that are interwoven. Those are the same forces that impact the river itself, which has long attracted heavy industry. Questions abound for these towns and this river in this era of climate change.

Marcus Hook takes care of us and our energy needs. But who's looking after Marcus Hook?

***************

Like a pair of proverbial 800-pound gorillas, two energy giants bookend Marcus Hook and dominate the landscape of this small borough on the shores of the Delaware River in Pennsylvania, adjacent to Delaware.

It's not surprising, really, the borough is tiny: Marcus Hook has a total area of 1.6 square miles, of which 1.1 square miles is land and 0.50 square miles is water -- the Delaware River. It has a population of 2,401 according to census data. Its median household income is $37,961 and 19.2% of its population lives in poverty.

So, half of its "territory" is water -- as befits a borough whose long history is tied to shipping -- and another sizable chunk is occupied by the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex, formerly the site of Sunoco Logistics. Monroe Energy, the other, bigger giant, is mostly in Trainer, Pa., but has a toehold in Marcus Hook.

Because the borough is so small, there's no escaping the presence of energy infrastructure. It hems every view to the east and to the west, like twin motherboards grown giant sized.

What's more surprising is how the locals regard those giants: with a mixture of relief that they're still here -- when significant businesses close, it hurts the local economy -- and some combination of disinterest and distrust. After all, once bitten, twice shy.

"Better a thriving business than a shuttered one," said Sandra Cislo, 62, who has lived in Marcus Hook all her life.

Outside of this small borough, Marcus Hook might be best known as the end point for two controversial natural gas pipelines, Mariner East 1 and Mariner East 2. Mariner East 1 is up and running, Mariner East 2 -- planned to be running by this point -- is hitting construction and regulatory hurdles. (More on this here.)

But the ongoing battles over pipelines and fracking have a hollow ring here. The places where those battles are taking place are facing new infrastructure: fracking sites, pipelines and compressor stations. That's a lot for those communities to contend with, along with the consequent threats to clean air and water. Here, energy infrastructure is old news. This community has had a long relationship with the energy business, and now most are simply grateful that the taxpaying businesses are back up and running.

That gratitude is easier to understand when you remember that in 2011, both companies announced they would close and the shock of that still resonates with people in the community, even though both sites are back in the energy business.

Marcus Hook, for all its small size, is a community that confounds easy judgments. Like an iceberg, what you see is only 10 percent of its story.

"A quaint little town"

So what's it like, having Sunoco (yes, I know, the company isn't called that anymore but that's how people here still refer to it) and Monroe Energy as neighbors?

Marie Swanson moved here 27 years ago. "I raised four kids and three grandchildren here. It's a quaint little town. Monroe (Energy) is on one side and Sunoco Logistics on the other: Never been a problem."

That's interesting. "A quaint little town" isn't the first impression that you get of Marcus Hook. Some of the housing is in good condition, but much of it isn't. About 50 percent of the borough's housing is owner-occupied and the rest is rental.

And there are, as Bruce Dorbian, Marcus Hook's director of Planning and Development, puts it, "some good landlords and some not so good." The borough demands that rental properties have a safety inspection annually, and to mitigate some of the problems that plagued the borough a while back, there is a requirement that a sprinkler system be in place for rental properties. In addition, the price of installing such a system may work to prevent absentee landlords from buying property for easy money.

There's no public housing, per se, but the non-profit Marcus Hook Community Development Corporation offers some rental properties, about 10, which are not income restricted says Dorbian, out of about 400 to 500 rental properties in the borough.

The rents charged are fed back into the MHCDC for rehabilitating dilapidated properties to make them habitable again, and put on the housing market looking for owner occupiers. The MHCDC is run by a 21-member board, with seven members each from local businesses, residents and borough officials.

There's very little of what used to be called Section 8 housing, though now its name is the Housing Choice Voucher Program. Many of the people who are in those properties, as well as in MHCDC, are senior citizens on fixed incomes.

The price of houses tells its own story. Checking a local/regional Realtor -- Long & Foster -- there's a 3-bedroom house listed for $45,000. Another for $50,000. Some reach as high as $135,000 but all of these prices are pretty amazing considering that you're 20 miles from center city Philadelphia.

One of Long & Foster's Realtors, Michelle A. Holloman, has lived in Marcus Hook, and now lives "next door" in Trainer. She echoes the enthusiasm for the little town: "It's a hard-working community, with good people." It's quite remarkable how often people hit on that note of pride in the community and most comment on how hard-working its residents are.

Lorraine Daliessio explains that she bought her house in Marcus Hook in 2012, when she retired. "The energy companies might keep people from buying a house here," she allowed, but she's emphatic: "This little town is a jewel."

Holloman also acknowledges that the presence of the oil and gas industry does have an impact on house prices, and an urban feel brings its own pressures.

"Look, it has the usual issues with a large number of people living in a small area," she explained. "There are about 800 homes in Marcus Hook. You have homeowners, landlords, renters and squatters."

There have been tough times for the housing market over the past 10 years, but Holloman sees -- as any good Realtor would -- that there's an upswing in the works. She sees more first-time buyers looking in Marcus Hook. "It used to be really bad with vacant properties, and houses broken into for people to steal pipes, but that's changing. I'm seeing more homes starting at the $100,000 mark."

Bobby Hughes, the borough's code enforcement officer and an assistant engineer with the volunteer Marcus Hook Trainer Fire Department, agrees with her assessment. Asked if Marcus Hook is coming back, Hughes replied with an enthusiastic "Absolutely!"

"I see people fixing up properties. I see some asking prices of $140 - $170,000. I don't think they'll get that, but the prices are going up," he said. "It's a good sign for the community."

Hookers and old hookers make the community stronger

Marion Grayson-Peden, 52, has lived here since she was 35. She and her wife recently purchased their home in Marcus Hook, next door to where Grayson-Peden already owned a home. They're hoping to make the two houses into one and are living in Ridley Park, Pa., in the meantime.

Most summers growing up, Grayson-Peden lived in nearby Chester, Pa., with her grandparents and knew of Marcus Hook as a refinery town. "They would always say they knew which way the wind was blowing. One way, it smelled of refinery, the other it smelled of an incinerator out toward Aston."

"Back in the 70s when I was growing up, the Hook had a wild and wooly reputation, with a motorcycle gang called The Pagans," she remembered.

Grayson-Peden's father was a principal in Chester, and she recalls he had a particular fondness "for the parents in the PTA, no pretention with them. They had a sort of honesty. It's the same sort of feeling I have in Marcus Hook. On my block," she said, "they're just the right level of nosy," and laughed.

"It feels like where I grew up. On Halloween, everybody is sitting on their front porch handing out candy. You know your neighbors." Growing thoughtful, she added: "There's a certain level of vulnerability, of intimacy. Neighbors here don't seem to be as guarded. They have a good sense of self-deprecating humor."

"I feel safe here. I feel like I belong here. I can be me."

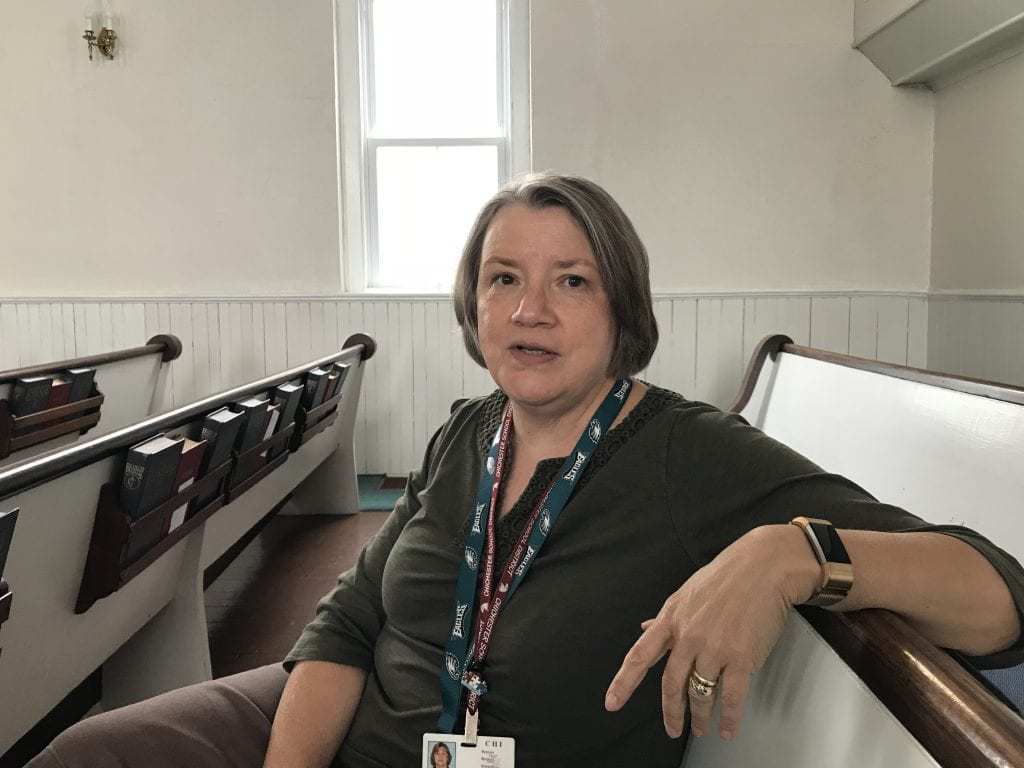

" 'Hookers,' we call ourselves" said Sandra Cislo with a smile. "Or 'old hookers'" Bigger smile. She's the pastor (yep, you read that right) of the Cokesbury United Methodist Church on Market Street and she is also the state and federal programs liaison for the Chichester School District, which includes Marcus Hook. Cislo has lived in the Hook all her life. She has two grown children, both graduated from college and both still living at home.

"I grew up with it in my blood. This is my community. Both my husband and I have college degrees. We chose to live here."

These are sentiments echoed by Hughes, who is the father of three young children (a boy, 9; a girl, 6; and a boy, 2.) He's lived in Marcus Hook for 37 of his 38 years. He also holds elected office: PA State Constable 3rd Precinct Marcus Hook.

"First things first," he says, "I'm not living here because I'm required to. I choose to live here."

"I love this borough. I was raised here, went to school here."

"I think I'm pretty successful," he says. "The majority of my friends from here have done well for themselves."

Even so, he recognizes that the community has changed over the time he's lived here. "In the past, I knew everyone, from senior citizens to the kids I went to school with. Now, there's much more turnover. People come and go. There's not as much community involvement."

"The change started to happen even before the refinery closed," he said. "When I was a kid, Sun Oil funded everything," and kids' sports drew enthusiastic support from the community.

Gradually people changed, he said, and once the refineries closed, there wasn't the financial support.

"First we ran out of kids who were interested, then we ran out of adults." Now most kids are involved in sports in Chichester, a bigger town just north of Marcus Hook.

People like Hughes, Cislo and Grayson-Peden are what Borough Manager Andrew Weldon is referring to when he calls them the bedrock of the community. He's concerned that the borough is losing some of its older, long-time residents. So the change continues.

Jobs

One of the reasons I supposed that the people in Marcus Hook supported the natural gas hub is for the jobs that they offer.

Not so, said Weldon, the borough manager. He knew of very few jobs held by Marcus Hook residents at the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex. Of course, there's a confusing jobs picture that emerges from the site since it has reconfigured itself.

Much of the work there has focused on the changeover from refinery to natural gas hub. Some of the work on site has been in dismantling the old equipment and installing new.

Also, the site is smaller and the feeling among many in the Hook is that most of the jobs that are permanent, full-time are for highly trained people.

Hughes noted that if the natural gas hub is going to hire 25 people, only one will likely be from Marcus Hook.

"And if somebody is lucky enough to get hired as an operator, chances are that he'll be moving away," he said.

Asked about jobs held by residents of Marcus Hook, Vicki Grandado, media relations for Energy Transfer Partners, wrote: "I do know there are some family members of residents who work at the facility and a number of contractors who live in Marcus Hook, but beyond that we do not comment on employees."

So, some jobs, but not a lot. There are more residents of Marcus Hook working at the Trainer facility -- Monroe Energy -- because that's a refinery, much like the old Sunoco facility in Marcus Hook. A different sort of worker would be needed at the natural gas hub than at the refinery.

A ton of phone calls to various unions in the area went unanswered so I suppose this video tells their story -- it was produced by Sunoco/ETP and it's painting the best possible picture. This point of view (union jobs) is valid, but you can see its bias in the title: Mariner East Pipeline Creates a Better Way of Life

Here's the video.

Everything old is new again

Remember Swanson's comment about Monroe Energy? That's the other gorilla that bookends Marcus Hook. It's located next door in Trainer, Pa., but you can see both from most streets in Marcus Hook. Monroe Energy is owned by Delta Airlines, and was purchased by the airline as a way to reduce fuel costs. In the tempestuous gas and oil business, there is now some thought that it might have been an unwise move and just recently, Delta announced that it was looking for a partner in Monroe Energy.

Even over the phone, you can almost see Bruce Dorbian the borough's director of planning and development, waving his hand, stating that discussions like these are not his concern. He has to focus on what he knows, and from what he knows, Delta's search for a partner in Trainer will have "no impact that I can see."

Dealing with unpredictable business operations is a long-standing tradition in Marcus Hook. Back in the 1700s, pirates used to prey on shipping on the Delaware and one of them, the notorious Blackbeard, is said to have frequented Marcus Hook.

While the Marcus Hook Preservation Society admits there's "currently no evidence to support it," there's a local oral tradition that Blackbeard used to visit his mistress at The Plank House, the oldest building in the borough. There's some serious archeological activity focused on the building and there's also some serious play: An annual Pirates Festival in the autumn that draws enthusiasm from pirate-lovers everywhere. Check out a huge collection of this year's festival photos here.

Shuttered businesses (like pirating) don't usually have such a happy ending, but businesses come and go in Marcus Hook.

There's a map in the council chambers that helps tell the economic history of the town. It dates from about 1915, and you can clearly see The American Viscose Plant, which was established in 1909, and employed about 600 workers to produce a relatively new synthetic fiber, rayon.

The factory ceased production of rayon in 1954 (jobs lost) but two years later started making a related product, cellophane film (jobs gained). By that point it was owned by a different company, FMC. When that closed, there were about 580 jobs lost. So there it is again, up and down.

While it was up and running, American Viscose was a significant local employer, and not just because of its jobs. Following an English tradition (its parent company was a British firm) it built employee housing, which still stands. The Village -- it's still called that today -- was designed by Emile G. Perrot, influenced by English prototypes. The Village was 261 two-story brick houses, two boarding houses and a store just across from the factory.

On that map in the council chambers, you can see that it was planned around a small park, with streets that radiate from the park.

They still do. That park now houses one of many veteran memorials scattered around the small town. All are well cared for, with flags that flutter.

"Marcus Hook is a very patriotic town," Hughes points out.

Dedicated on October 1949, the Sun Seamen's Memorial faces the Delaware River at Delaware Avenue and Green Street. This memorial commemorates one hundred forty-one brave officers and seamen who lost their lives in World War II while serving aboard Sun Oil Company tankers. PHOTO COURTESY OF SUNOCO/ETP

This memorial is dedicated to those who lost their lives in WW2 - on ships such as the SS Atlantic Sun, and the MS Sun Oil. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

The Village is still considered among the best housing in Marcus Hook. In the 1940s, and '50s, the company sold those houses to its workers and according to the notes about the village on the Marcus Hook website, "original buyers or family members are still living in these unique homes." That might be the root of the very strong community pride that is really close to the surface as you get to know the residents. More about the village here

Oil, gas and pipelines are old news here

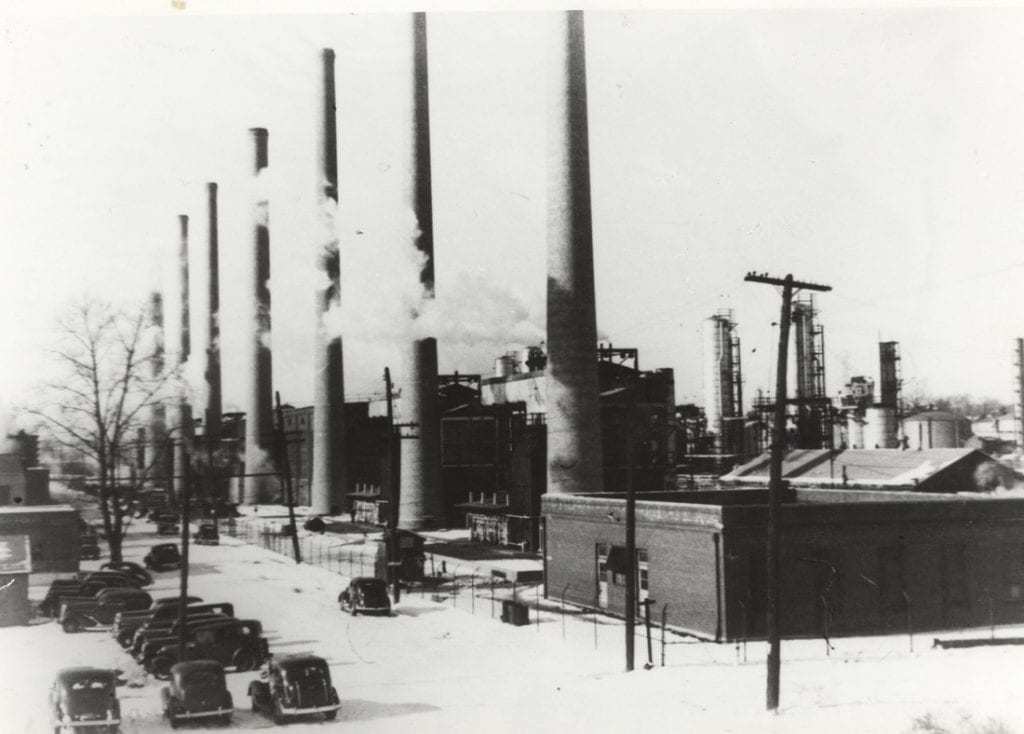

Also on that map, there's evidence of why the town isn't all that het up about its neighbors. The oil and gas industry has been a part of Marcus Hook for a very long time, certainly since the date of this map, 1915. Back in 1901, Joseph Pew bought 82 acres here, likely attracted by the deep-water port on the Delaware River and access to the trade it provided.

Where the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex now sits, its parent, the Sun Company, used to sit, sharing the present property with the Atlantic Refinery Company, which straddles the border between Pennsylvania and Delaware.

And pipelines? Yep, been there, done that: The United States Pipeline and the Pure Oil Pipeline are on that map. The oil and gas industry has been part of Pennsylvania's story ever since the famous Colonel Edwin Drake sank the first oil well in the country in 1859 not far from Pittsburgh.

It might be useful to think of Marcus Hook -- and the Delaware River -- as a sort of gateway that energy companies have used, and still use, to import or export oil and gas into Pennsylvania or out. The Mariner East 1 pipeline is a reuse of a pipeline that was in use before the current fracking boom.

The pipeline now carries shale products to Marcus Hook, where trucks and trains and ships can carry it further afield.

Until the plant was closed in 2011, it was a Sunoco refinery, processing imported crude oil. Then came shale gas, and a new name for a new venture. Sunoco Logistics merged with Energy Transfer Partners in April 2017, and the site is owned by Energy Transfer subsidiary Sunoco Partners Marketing and Terminals.

But the locals still call it Sunoco.

Whatever its moniker, it is a natural gas hub not a refinery. It occupies a much smaller footprint in the Industrial Complex and its main focus is on natural gas liquids from the shale fields farther west. According to a press release, it "has built six tanks storing more than 2 million barrels of propane, ethane and butane to support our Mariner East 1 and Mariner East 2 pipeline systems."

"Some people say, 'We need that pipeline,'" says Grayson-Peden, who's lived in Marcus Hook for nearly 20 years. "I'm not sure we can count on that, watching the political temperature. It's more of a last gasp, and I'm not sure we can count on Sunoco for our future."

Pipelines, etc., may not be the best hope for a bright future

There are lots of people who would likely agree with that train of thought, especially environmentalists like Joe Minott, the executive director of the Clean Air Council based in Philadelphia. He feels strongly about pipelines -- and natural gas -- taking us in the wrong directions

"Communities are being presented with false choices these days. We should be moving away from all fossil fuels," Minott said. "Not toward natural gas, where methane is 86 times more harmful (to the environment) than carbon dioxide.

"Even if you are a strong proponent for natural gas, and the Mariner East 2 pipeline, we don't have the regulations in place and the state doesn't have the people power to monitor and enforce the regulations we have.

"Each time there's a new pipeline, we should be asking what is the pipeline going to do?

"No one has taken the time to figure out if this is good for Pennsylvania or Pennsylvanians.

"Most of these pipelines will be orphaned in my lifetime," he concluded. Not the most reassuring words for Marcus Hook to be hearing.

Minott isn't arguing with Marcus Hook, but rather with the state and federal policies that aren't addressing the real need to move away from fossil fuel industries as being the answer for communities like Marcus Hook.

He bemoans the investment of "millions and billions in fossil fuels," which "just delays us."

"Nobody is focusing on the transition from fossil fuels," Minott says. "We should be moving toward a green economy for jobs now and in the future.

"Pennsylvania is falling behind the other states in the green economy -- and communities are still dependent on fossil-fuel industries for jobs and a tax base.

"Coal is dying, not because of anything I've done, but market forces. Now it's natural gas, we don't need it. Most of it is being shipped overseas, despite damage to local ecology, to drinking water."

One of the chief concerns for many local environmental groups is that the energy industry is bad for the river and for the whole watershed. The Delaware River Basin Commission is considering a ban on fracking in the watershed because of fracking's negative effect on water quality. Makes you wonder: If it's bad for the Delaware, it can't be great for the other areas where fracking happens and through which the pipelines run before they get to the Hook.

Shock waves in southeast Pennsylvania

Grayson-Peden remembers when the refineries closed. "It was kind of scary. A lot of people were not just scared but angry. There was a lot of animosity toward Sunoco. All these years we've played ball with you and now you've screwed us."

She remembers that businesses faltered and some closed: "There was a lot of concern. A lot of worries."

Hughes remembers it too: "When the refineries closed down, the town shut down."

The closure in Marcus Hook in 2011 was only one of three thunderclaps that hit the southeast corner of Pennsylvania where there were three refineries that announced they were shutting down. The most massive was the Sunoco facility in South Philadelphia, one of the largest on the East Coast. A little farther south was the Conoco refinery in Trainer, and the Sunoco refinery in Marcus Hook, the smallest.

Refineries were a significant part of the fabric of life in Delaware County and in nearby Philadelphia, bringing in taxes to support the various towns, counties and school districts where they were located and supplying those elusive family friendly jobs. Thousands of good jobs were going to be lost. People who don't live next door to an energy facility -- or for that matter near a coal mine -- are often confused by the desire of local residents to hang on to what seems "dirty" industry that might offer good pay but not great health conditions. But often, when those good-paying jobs disappear, there's nothing else that will support a family. Sometimes that means families have to work harder for less income, or sometimes it might mean moving away.

It's too simplistic to pit the good jobs versus bad air in one of the endless arguments that feed political stalemate. But there is a problem with the air in Delaware County and in Philadelphia, according to the American Lung Association, which gave the two counties an "F" for ozone aka smog.

According to Philadelphia Magazine, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency explains that smog is formed when toxins emitted by cars, power plants, industrial boilers, refineries, etc. react in the presence of sunlight. Smog is more prevalent in the summer months due to the increased sunlight and warmer weather.

Philadelphia received a "C" for particle pollution, Delaware scored better with a "B."

Even so, life-long resident Cislo does not have any issue with the air in Marcus Hook and never had a lung problem. Look again at those scores: Remember that all of Delaware County and all of Philadelphia get a "D" on air quality, so whether you live in a $75,000 home in Marcus Hook or a $2 million one in Villanova, you're still breathing the same air -- part of southeastern Pennsylvania's legacy of energy businesses.

So finding a balance to our energy problems is not a question that Marcus Hook should answer but an issue for the larger community, the state and federal government.

Back to 2011, the shock waves from those announcements are hard to imagine, but really well told in a report issued in 2012 by Temple University's Center on Regional Politics:

"Taking Care of Our Own: How Democrats, Republicans, Business, and Labor Saved Thousands of Jobs and Our Refineries."

You can find it here

That report tells the story of how the three refineries were rescued and how they became what they are today. Marcus Hook became a natural gas hub, Trainer was bought by Delta, and the largest became Philadelphia Energy Solutions. We've already seen that there are rumors that the future of the Trainer facility might become complicated. And the PES sought bankruptcy protection earlier this year. The optimism that is expressed in that report has not been fully realized.

Except, maybe, and maybe surprisingly, for the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex.

By 2011, fracking was an economic force to be reckoned with, and the transport and processing of shale oil and gas would have been of intense interest to the energy industry. Of course, this wasn't refining as had been the focus of the Marcus Hook site, but a repurposing.

As Bruce Dorbian recollects, "As they announced the plant's shut down, various spokespeople told us they had various ideas going forward to address some sort of redevelopment of the site.

"You know, it's kind of a thing of them saying 'Trust us.'" Dorbian remembers this and there's still a note in his voice that implies that trust wasn't easy.

"After all, they're a publicly traded company, they don't really care about Marcus Hook. Shareholders only care about the bottom line.

"So they had a plan, but we weren't in on it," he concluded.

In the meantime, Marcus Hook officials had to look after Marcus Hook. Without Sunoco, there was going to be a massive shortfall in taxes. They were staring bankruptcy in the face. In Pennsylvania, there's a process for financially distressed communities run by the state's Department of Community and Economic Development, Municipalities Financial Recovery Act. Commonly referred to as Act 47.

With that looming, the state acted to get a financial analysis of the borough and started developing a plan for the borough to avoid Act 47. Mostly because of the development of the natural gas hub, Marcus Hook never became an Act 47 municipality.

As told in the report out of Temple, there was a lot of energy being put into rescuing the lost jobs and lost taxes from the refineries shutting down. Behind the scenes, people like Patrick Killian, director of the Delaware County Commerce Center, were meeting with industry representatives, other government officials on the state and federal level as well as union representatives. In addition, since the Philadelphia plant was one of the largest in the East, there would be a significant impact on the availability of oil in the Northeast, which would mean scarcity and a price increase. That's not good for any stakeholder.

Have I mentioned that these closures were a great big deal?

Killian recollects that the conversations that led Delta to the Trainer facility were easy. Not Marcus Hook. That facility "was a difficult challenge," he said. "Two studies were commissioned with two important objectives in mind: What would be the most effective use of the 400-plus acre site and what would generate the most stable economic conditions?"

It became clear that one of the best uses would be as a terminal for the shale gas that needed to come to Southeast Pennsylvania from Southwest Pennsylvania, Killian said.

"The site needed an awful lot of retrofitting and that supplied work to hundreds in the building trades," he said. "The site has some unique advantages: deep water access for shipping; underground caverns to store product. And a community in Marcus Hook that was welcoming and understanding of heavy industry. They've lived with refineries for a long while and they welcomed the work.

"The future of the Hook is stable," Killian says. Especially in light of the new draft IRS changes to the revenue code that will allow investment funds to offset capital gains if those funds are invested in Federal Opportunity Zones, a designation that will come from the state.

He sees the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex as being in an ideal position for expansion partly because of the investment that could flow there but also because with the shale gas and oil coming, there will be other sorts of industries that would likely avail themselves of close proximity and save transportation money, much as Braskem does with its polypropylene plant. It leases space in the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex.

But Minott sees this bright possibility more warily: "I'm incredibly sympathetic to communities like Marcus Hook. They're grabbing at straws -- these industries close and the jobs go and the tax base falls.

"Look at PES (Philadelphia Energy Supply -- the reboot of the large Sunoco facility) they don't have a plan, and it declares bankruptcy and no one knows what to replace these good jobs with. Everything is short term -- the politicians only want to get re-elected and the communities get screwed."

Taxes

Talk taxes and you'll bang head first into the economic reality of running a town like Marcus Hook.

The first job was to avert the Act 47 status and not fall under the state's oversight. And not just the borough -- there was going to be a revenue shortfall for Delaware County and the Chichester School District, which includes Marcus Hook, Trainer, Upper Chichester and Lower Chichester.

Knowing all the background, you'll be able to appreciate this video from Energy Transfer partners, where we see "Sunoco Pipeline partners join local officials to announce an agreement for a reassessment of the Marcus Hook Industrial Complex. The improvements made there will net the Chichester School District, Delaware County, and Marcus Hook an additional $4.8 million in property taxes."

The reassessment was welcomed by all three entities. Property taxes were still paid while the property morphed from an oil refinery to a closed business to a natural gas hub, and certainly were less. This past year, taxes for Marcus Hook from Sunoco/ETP increased to $1,050,000. The borough will still feel a squeeze as there's been a reduction in the Earned Income Tax that all residents who worked at the refinery paid because the number of workers dropped from about 600 to about 50/60.

Dorbian explained that that revenue is likely gone and not coming back, partly because there are fewer workers at the site, partly because when workers live in other boroughs and towns, more of those towns are levying their own tax.

But the energy companies are contributing to the community once again, says Hughes. The Marcus Hook/Trainer Fire Department gets a lot of valuable fire-fighting equipment from Monroe Energy, Sunoco, Braskem and Honeywell. And the firefighters are trained in the special work that an emergency situation at one of those facilities might present.

There's also a special firefighting school in Texas that both Monroe Energy and Sunoco/ETP pay for a firefighter to attend.

No simple answers

So, there's a part of the community that's welcoming of the newly revitalized Sunoco/ETP plant. But the picture isn't so simple.

In the middle of a conversation with Norman Mirat, the owner of Michael's convenience store on 10th Street, an older man walks in, plunks down some money and asks for four cigarettes. Not four packs, but four single cigarettes.

Gathering his supply, he walks back out of the store.

His is yet another face of this complicated borough.

"Marcus Hook is a broke town," says Mirat, who's been here for 12 years. "It's always been broke."

"Nobody who lives in Marcus Hook loves Marcus Hook. Everybody who lives here wants to get out. Eighty percent of the people I see in my store are on food stamps or Social Security."

About three blocks away is Munro Printing and Graphic Design. John Munro is the owner and he says he's happier with his business after moving to Marcus Hook from Trainer. "The people here are all good. Best move I could have made."

If there are 2,000-plus residents, it's not surprising that everyone sees the Hook from their own vantage point.

Grayson-Peden got married a few years ago and she told her wife she had two conditions:

First, that her wife wouldn't interfere with her faith. (Grayson-Peden is very active in Cokesbury United Methodist.) "You don't have to share my faith beliefs but don't undermine them."

Second, "We have to live here."

Her wife's response was an incredulous "We do?"

"I love the church, but even if the church weren't here, I'd still want to be here."

The very imposing Municipal Building houses the borough offices, the library and the police station. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

The tiny "downtown" never really came back after the closing of first the Viscose Factory and then the Marcus Hook oil refinery. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

One of the rumbling black trains that ferry oil and gas products into and out of Marcus Hook. Some crossings are well signaled, some are not. PHOTO BY MEG MCGUIRE

******************

So many people helped me understand at least some of the story of Marcus Hook. If there's something not quite right, it's me not them!!

First, Borough Manager Andrew Weldon, who put up with endless questions, and the borough council, who allowed me time with them to begin this story. Bruce Dorbian, who has worked for the borough for 35 years and is now director of planning and development. Patrick Killian, director of the Delaware County Commerce Center. Joe Minott, executive director of he Clean Air and his specialist in all things Marcus Hook, Alex Bomstein. Another helper (especially with that land use map) is Michale Ruane from the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission. Vicki Granado from Energy Transfer Partners. Adam Gattuso from Monroe Energy. Marcus Hook's knowledgeable librarian, Irene Wallin. The owner of Michael's, Norman Mirat. The owner of Munro Printing, John Munro. And a host of others who offered their insights: Marie Swanson, Michelle Holloman, Lorraine Daliessio, Bobby Hughes, Marion Grayson-Peden, and one of my first contacts, Sandra Cislo, who opened many doors for me. Thanks to you all for your time and interest.